|

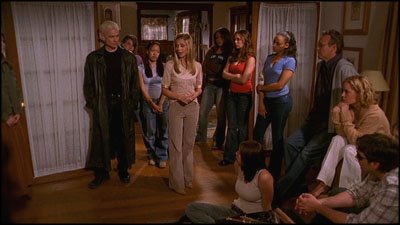

| Former villain Spike, Buffy and the Potentials |

Similarly, we also fear our scientific efforts to improve society. In a world that has not only witnessed the horrors of Nazi eugenics experiments and genocide but also the syphilis experiments secretly conducted on Blacks in the United States, it is easy to see why. Big Brother is alive and well in a country that passed the Patriot Act, which allows for heightened surveillance and arrest of those suspected of being political enemies of the United States. The average American’s behavior is photographed and recorded innumerable times each day. We would be crazy to not be afraid of the abuse of such technology.

|

| Duel, 1971 |

|

| Dawn of the Dead, 1978 |

Along with our fear of insanity, science fiction offers some variation on all of our fears. The Frankenstein monster becomes HAL of 2001: A Space Odyssey and the replicants of Blade Runner. Vampires take over the Earth in Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend and The Omega Man. Our inner wolf is unleashed in the insanity of the rageaholic zombies of 28 Days Later. Not all sci fi but kindred, the new gothic heroines of Resident Evil, Underworld and Buffy the Vampire Slayer face all of these monsters and the infinite variety of madness, helplessness and alienation that causes them and is caused by them.

The future is the place where horror and science fiction become all but indistinguishable, but there are important common denominators in the vision. Science fiction horror is, in the main, a world of repressive order (dystopia) or a world of chaos. The great fear that connects these two visions lies in a distrust of human nature. We don’t trust our own ability to deal with what's coming our way.

What we expect and most fear about the future is a time of reckoning. We are afraid of that moment when we must face our fears and deal with them. On a crucial level, we are afraid of that moment when we can no longer take refuge in our child-like innocence, but we absolutely must take responsibility for setting things right. This fear binds horror and science fiction with yet another sibling, fantasy.

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, all of the elements of the horror reckoning exist in a world born out of mythology and our childhood imaginations. As with most horror, the fate of the world of the story lies in the hands of a very small number of people, the fellowship of the ring, several members of which hold nothing like real power in their mythic universe. But they do have a grasp on key secrets. And when they understand what needs to be done, they are bound together to achieve that goal. From the Ring Wraiths to the Balrog to the armies of Samoran and Sauron, monsters abound and threaten their quest, but the key to the future lies in the hands of the least of them, a little, unambitious, man-like creature called a hobbit. Though the hobbit would rather do anything than take the world on his shoulders, he alone might slip past the radar of the evil threatening the land, and so he sacrifices himself to do what he needs to do.

|

| Van Helsing and Vampire Slayers, Dracula '31 |

And then there is always that one member of the group whose role is slightly more important than that of all of the others. That individual—Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings, Jonathan Harker in Dracula, Father Karrass in The Exorcist, Buffy, the would be cheerleader—must ultimately face key elements of the horror alone. That character is the protagonist of the archetypal horror story, which means that is the character we are asked to identify with most closely. In other words, we read horror and many other genres of fiction tied together by this impulse, in part, to vicariously experience what any sane person fears—what it’s like to know the fate of your world lies in your own hands and what it takes to rise to that occasion.

|

| The Exorcist, 1973 |

Our fears are justified in virtually all horror mythology. The protagonist often dies—if not in the course of the final battle, then as a consequence after the fact. But what each of these characters has decided is the most important part of the ethos. His or her greatest fears, and even the protagonist’s individual survival, are less important than the call of the moment, the larger responsibility. In the film version of The Exorcist, Father Karrass cries “Take me,” and carries Ragan’s demon out of the window to the street below. As with many horror resolutions, the monster may not even be destroyed, but it has been derailed from its present task, and other lives are saved by the martyrdom of the protagonist. Reaching back to its gothic roots, the crucifixion of the horror protagonist may be the most common Christian element.

Some of the more self aware versions of these myths recognize the need to liberate such concepts of death and resurrection from traditional Christianity. In the epic television show, Buffy, The Vampire Slayer, the young heroine must not only sacrifice her own life (more than once), but she and the fellowship she left behind (playfully called the Scoobies) must wrestle with their toughest challenges after her resurrection. Her teacher, Giles, must learn to be a student; her eternally boyish friend Xander, must learn to be a man; and her most powerful friend, the witch Willow, must learn to take control of forces that once overwhelmed her. Buffy herself must even give up her unique role as savior to unleash the power in the world’s potential slayers.

In Stephen King’s Dark Tower series, every member of the fellowship (in this case called a ka-tet) must face his or her own death, in effect destroying even the ka-tet itself. Even King, the writer as a character, must reckon with what might have happened if he didn't survive being run over by a van on June 19th, 1999. In this epic’s particularly bleak outcome, the only slim chance that the future might be saved lies in the act of storytelling itself.

|

| The Dark Tower's ka-tet |

|

| Buffy's "ka-tet" of Slayers, Potentials |

While most traditional horror and fantasy calls upon some form of divine intervention to set the world right, virtually all of it asserts that (culturally, socially and politically) insignificant, often misfit, characters play a crucial role in the world’s redemption. What all three of these great series ask is how we respond if whatever divinity exists has failed us. Then we are faced with our greatest fear—the future is up to us. It doesn’t get much scarier than that. It also couldn't be any more necessary.

|

| The Walking Dead "ka-tet" |