Everything I was trying to talk about 3 posts back with "A Little Respect," made unforgettable in a poem by Lee Ballinger. DA

Shakespeare's In the House

In the fall of 2003, at a public forum at the Teacher's Union building in downtown Los Angeles, Luis Rodriguez said:

In school

They want you to study Shakespeare

I'm here to tell you

That you can be Shakespeare

*****************************

Mill rat, hard hat

I used to pour steel down by the river

Working double shifts, having family rifts

Burnt skin

Meant the rent would be paid

I was standing in a ring of fire

When my fifteen minutes of fame came to call

I wrote a book on sports

Controversial

But not enough to end up in the courts

I had to work it

When I wasn't working

Every time I got a day off

I was on a plane

Like James Brown's "Night Train"

Atlanta, Birmingham, Philly and DCLA, Kansas City, Chicago, Houston too

What's an Ohio boy to do?

Do interviews

Be on the news

Get up early for TV shows

Stay up late for guest DJ flows

That didn't mean I got respect

Howard Cosell called the anchorman

With that voice like a squashing inner tube

"Was the young man eloquent?"

"Yes he was!" Howard was told

But Wide World of Sports lost the tape

Or so they said

Then the writer from Sports Illustrated got his education up

Sneering "No steelworker does my show!"

I wrote two guest pieces

For the New York Times

All the news that's fit to print

Now included me

Yes, the welcome mat was out

But at an angle

The editor there said

Right to my face

"I had no idea a steelworker could write so well"

He asked me where I went to college

Where did I get my knowledge?

He tried to cast me as the accidental tourist

But I didn't fit that role

So I wasn't gonna fake it

When I said I didn't finish high school

That I had no cherished "my school"

He thought I was lying

He suddenly stopped trying

To connect with me

Back in the mill

It was another story

A tap on the shoulder

"Someone's here to see you"

Over from the furnace

Down from the crane

Working the rails

Now in from the rain

They came up to my platform

Awkward

Uncomfortable

"You're the guy I saw on TV

I thought you might understand"

They put a poem or a tape or a drawing

In my burned, calloused hand

Come out, come out wherever you are

We were made for life's journey

We were born to go far

My friend Cristina

Was filled with music inside

Four kids, two jobs

She never got to take it for a ride

So it fell a generation

And landed with a thud

Her son Hector

Was the living, breathing incarnation

Of Chuck Berry's Johnny B. Goode

Hector could play a guitar like ringing a bell

Had perfect time

A knack for rhyme

His songs could beautify hell

But….His pants were so low

His bald head so mean

He got a gang jacket

At the age of fourteen

Kept doing time

Nowhere to be seen

So Hector's gift was tested

From below and above

Bands fell apart, he put 'em back together

To play the songs he loved

One night in the IE

He had a party for his new CD

I danced with Cristina

So I could hold her

While I told her:"When Hector's band starts to play

I love to watch you sway

In front of your creation"

Come out, come out wherever you are

We were made for life's journey

We were born to go far

I was in an airport

Waiting out delay

The lady sitting next to me

Looked so familiar

But I just couldn't place her

Then…

There she was

On the front page of the paper on my lap

An Enron executive who'd lost it all

"I feel like a victim"

The article said

"A victim of economic terrorism!"

That's what I read

Lost her pension

Not to mention

"I almost lost my mind"

I tapped her on the shoulder

The words they just rushed out

"I always thought that everyone on an upper floor

Was just a whore"

Her head snapped back

Her anger flashed

She turned my other cheek and slapped it with her voice"Just a whore?"

Then a sigh, volume down"Just a whore?"

"Not any more. Not any more."

She turned away

But I couldn't miss what she'd been doing

With sketch pad and colored pencils

Deep, dark, and dripping

Bent low but spirit strong

Come out, come out wherever you are

We were made for life's journey

We were born to go far

******************************

So many of us

Just accept our place

We listen to the voices which anoint just a few

As worthy of a critic's taste

Who are these gatekeepers

Who claim we got nothing to say?

Grant givers

High livers

Insisting they're superior even though…

They couldn't rhyme Pete Rock

With sheet rock

Why do we seek their approval?

Instead we should seek their removal

Cuz our dreams can't come true

Tucked away in unread pages

Or nestled in the notes

Of silent, stillborn rages

Come out, come out wherever you are

We were made for life's journey

We were born to go far

****************************

In school

They want you to study Shakespeare

I'm here to tell you

That you can be Shakespeare

LB

Friday, January 05, 2007

Wednesday, January 03, 2007

Those Bills Don't Just Go Away

(Reason #14)

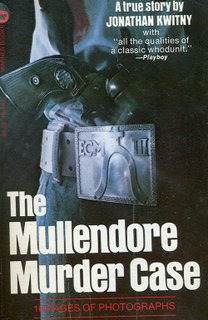

I just finished a great little book called The Mullendore Murder Mystery, a book that's been sitting on my shelves for three decades but gone unread. I bought it when I was probably 11 or 12 because it was about the murder of a prominent rancher outside of my hometown, a story I'd first heard about the year it happened, when I was 7 years old on one of those Christmas Eve family drives to look at the lights. I believe we drove by the Mullendores in-town residence, and what my parents talked about from the daily paper stories must have fired my imagination.

I couldn't really read that book when I first bought it because it is largely a story of debt spiralling out of control, while E.C. Mullendore, the doomed protagonist dips into murkier and murkier (and ultimately deadly) territory trying to pull his ass out of the fires that rage when spending exceeds profits. Wall Street Journal reporter Jonathan Kwitney actually manages to balance the number crunching necessary to see where ethical fudging blurs into outright theft and fraud time and time again with a human story about as manic and scary as anything in Goodfellas. In the process, Kwitney (later the author of the indispensable profile of U.S. relations with Africa, Endless Enemies, and the scary story that connects the Southeast Asian Golden Triangle to Iran Contra, Crimes of the Patriots) also lays the groundwork for a crucial perspective on the last half century of the relationship between business and politics. For instance, one of the key players in The Mullendore Murder Mystery, Houston powerbroker Morris Jaffe would later be an important force behind Democratic and Republican presidential campaigns and the S&L scandals.

But the thing is, in terms of my recent Marx blogging, the Mullendore story is a thought provoking portrait of what happens when an American romantic, or a whole clan of American romantics, fails to reckon with his contradictions and the material world around him. It's the story of one runaway train in a culture made up of runaway trains. This is precisely the lack of perspective Marx sought to remedy.

From Monsters, Marx and Music--

“Active social forces work exactly like natural forces: blindly, forcibly, destructively, so long as we do not understand and reckon with them. But once we understand them, once we grasp their action, their direction, their effects, it depends only upon ourselves to subject them more and more to our own will, and by means of them, to reach our own ends.”

--Friedrich Engels, “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific”

In Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials’ the heroes divine the truth and navigate their way to reckoning with the help of a compass, a knife and a spyglass. The navigational tools Marx offers are a few terms and relatively simple matters of logic. At the heart of these ideas lies a matter of reckoning, the difference in beliefs and realities in the present tense and, in the future, a reckoning with the price we are bound to pay.

An awareness of Marx’s math built the labor movement in the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century, using worker unity to drive up the market cost for a better quality of life. The math that’s been forgotten in the past 60 years—since the Cold War effectively declared it un-American to think about these matters--has paralleled the fall of the labor movement, and the loss of job security and workplace benefits.

Marx started developing his ideas just as the rise of a new capitalist class began to break away from their former monarchies, the most familiar examples being the American and French Revolutions. Thinking people began to wonder about the discrepancy between the dreams of these revolutions and their realities. In America, a landowning class had certainly been elevated to a ruling class, but only by maintaining chattel slavery over African Americans. In France, the democratic revolution threw off a monarchy to be replaced by a reign of terror and, then, the autocratic dictatorship of Napolean Bonaparte.

Like his contemporaries who lay the groundwork for the electrical revolution, psychology and genetics, by the age of 25, Karl Marx began to understand that the path ahead lies in understanding our relation to the world around us. Marx, who recognized the role the Industrial Revolution and the capitalist system played in these revolutionary impulses, decided the only way to grasp these changes and steer them in a humane direction was to study the workings of the economy and unlock just how and why one class of people profits from these changes while the situation for others seems to worsen.

Within four years, he wrote Wage, Labor & Capital, a series of talks that would serve as a rough draft for Capital, the book he would spend the rest of his life writing—the first volume coming out when he was 49, the remaining two volumes consuming much of the last decade and a half of his life. These efforts seek to describe the essential math at the foundation of the social order, and they show both the fundamental injustice in that math as well as the cost of that injustice on individual freedom and happiness. What’s more, this math seeks to forecast the future, and what it predicts looks like the world around us—a path marked by profound technological progress and increasing wealth, yes, but one which benefits only a few while the relative quality of life worsens for the majority.

When I first read Marx, I was shocked by how well he explained the trajectory of world politics in my lifetime, starting with the economics of my hometown. I never understood why, in the early 1980s, the CEO of Phillips 66 could renovate his private jet, while my father and most of the other parents I knew, who had given decades to his company, were wringing their hands over the layoffs of thousands of their co-workers. Even more so today, it’s hard to see why Delphi in Detroit, for instance, gets away with selling out its own workers and destroying its old home market.

Most people come up with two answers, both based in the corruption of the CEO—short term thinking and greed. What Marx's math shows is the system demands that kind of thinking. not just in the CEO but system wide. Marx argues capitalism ultimately eats itself and any hope for long term human progress demands that we deal with the blind logic of the system.

Today, it’s actually easier to see why Marx’s logic rings true than it has been at any given point over the past 150 years or so since he first began to lay it down. That’s because Marx's predictions deal with the impact of economic revolutions that have taken place in a blip of time, less than 1% of human history.

While most people who quibble with Marx get hung up on the particulars of individual trees of that history, he is showing the cost of a slash and burn system to the forest as a whole. In 1848, when he wrote Wage, Labor & Capital, for instance, ultimately failed revolutions erupted all over Europe, and at various times since, such as the 1917 revolution that produced the largest country in the world, the ultimately doomed Soviet Union, or the Great Depression of the ‘30s or even the mass cultural revolution of the 1960s, it seemed the time for Marx’s predicted revolution was at hand.

But what he predicted was a revolution that followed the flowering of globalized capital, a process that has only kicked into high gear with the globalization policies of the past 20 years or so, which are creating the greatest threat to U.S. dominance in the autocratic yet capitalist state of China. To understand Marx, we need to keep that big picture in mind, and what may be the best way to see what one has to do with the other is to take a look at the broad strokes of Wage, Labor & Capital in light of that big picture....

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)