|

| (Brother James McGraw owned some version of this.) |

Kids who love horror recognize these complexities even if they can’t articulate them. They are drawn to monsters even though they know the contact will make them shudder. And they can smell the truth in a passage like the one in Robert McCammon’s novel, Boy’s Life, when he goes home after a particularly ugly run in with bullies and tapes his Famous Monsters of Filmland pictures all over his bedroom.

McCammon writes:

“I was never afraid of my monsters. I controlled them. I slept with them in the dark, and they never stepped beyond their boundaries. My monsters had never asked to be born with bolts in their necks, scaly wings, blood hunger in their veins, or deformed faces from which the beautiful girls shrank back in horror. My monsters were not evil; they were simply trying to survive in a tough old world. They reminded me of myself and my friends: ungainly, unlovely, beaten but not conquered. They were the outsiders searching for a place to belong in a cataclysm of villager’s torches, amulets, crucifixes, silver bullets, radiation bombs, air force jets, and flamethrowers. They were imperfect, and heroic in their suffering.”

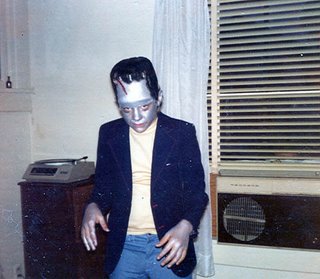

|

| The writer at 12, dressed as his favorite superhero |

This enchantment led me to strike a deal with my parents that I would go to bed early on Saturday nights if they would get me up at midnight to watch Mazeppa Pompazoidi’s Uncanny Film Festival and Camp Meeting. Hosted by Tulsa comedian Gailard Sartain (as a screw loose sorcerer named Mazeppa) and a handful of sidekicks (including Gary Busey, aka Teddy Jack Eddy), this shock theater package introduced me to the classic monsters of Universal Studios in a package of anarchic comedy that combined elements of Jonathan Winters, Ernie Kovacs and the 3 Stooges. For a six year old at the close of the 1960s, this was the beginning of my counter cultural education.

This enchantment led me to strike a deal with my parents that I would go to bed early on Saturday nights if they would get me up at midnight to watch Mazeppa Pompazoidi’s Uncanny Film Festival and Camp Meeting. Hosted by Tulsa comedian Gailard Sartain (as a screw loose sorcerer named Mazeppa) and a handful of sidekicks (including Gary Busey, aka Teddy Jack Eddy), this shock theater package introduced me to the classic monsters of Universal Studios in a package of anarchic comedy that combined elements of Jonathan Winters, Ernie Kovacs and the 3 Stooges. For a six year old at the close of the 1960s, this was the beginning of my counter cultural education.And it was empowering. From those nights in 1969 on, I watched and read about monsters all of the time. I too had a stack of Famous Monsters of Filmland in my room and monster pictures on my wall. I made the Aurora model kits of Frankenstein, Dracula, the Mummy, the Wolf Man, the Phantom of the Opera, Mr. Hyde, the mysterious tattered skeleton called the Forgotten Prisoner, King Kong and Godzilla. I drew monsters and I wrote about monsters, writing my first unfinished novels about a lizard man (The Lacertilian Experiment) and a giant squid (The Kraken) in fourth grade.

After my parents divorced and I was a latchkey kid in a new neighborhood with an old school, I was lucky to find a fellow monster lover in the only kid at my new school who dressed like me, Scot Billingsley. Scot and I made horror movies with my mother’s wind-up, Standard 8 (Green Stamps-trade) camera. Each roll of film was less than 3 minutes long, so these movies were little more than special effects reels, but we learned a good deal about horror make-up and how to make stage blood that was better than the stuff you could buy at the store (if only because we could make large quantities to splash around at a time).

After my parents divorced and I was a latchkey kid in a new neighborhood with an old school, I was lucky to find a fellow monster lover in the only kid at my new school who dressed like me, Scot Billingsley. Scot and I made horror movies with my mother’s wind-up, Standard 8 (Green Stamps-trade) camera. Each roll of film was less than 3 minutes long, so these movies were little more than special effects reels, but we learned a good deal about horror make-up and how to make stage blood that was better than the stuff you could buy at the store (if only because we could make large quantities to splash around at a time). We also made some pocket change every Halloween with elaborate spook houses put on in the Billingsleys' old garage out back of their house. We planned those spook houses for months in advance and even coaxed half the kids in the neighborhood into volunteering their services.

Honestly, I do not think I would be a writer today, much less a teacher of writing, if I hadn’t been turned on by the art of horror. And there's the heart of it. If Mary Shelley hadn’t written so powerfully about her feelings of alienation, I don’t know how I would have found these means to connect.

No comments:

Post a Comment