After three decades, I've all but hung up my rock criticism work, but I haven't really, and I don't suppose I ever really could. I just feel alienated from the forms it takes today. Maybe they were always there, and I was just too naive to realize it, but I don't want to write about music academically, I'm lame at boosterism (though my dedication to certain careers may get me labeled that way), and I have never felt my strength was as a consumer guide.

Recently, I took on an assignment to write about The Clash. And all around the periphery of what I'm writing I'm reminded why I started writing about music in the first place, why I cared about music writing in the first place. It was never about rock versus pop or whatever other genre--with some of their grandest moments pure disco exhilaration, bands like the Clash (and the Clash in particular) tore down such walls as soon as someone tried to block their options.

It was about "rock" as something bigger than a commodity crafted by an artist for the appreciation of a knowing audience. It was about rock as a concept that challenged our perceptions of a rigged system and gave us strength to be and think on a bigger scale. With a band like the Clash, you weren't simply a listener, you were part of the action....and that meant everyone....the 16 year old kid I was chording alone with my records on a Hohner guitar my girlfriend bought me, friends who rode together under Oklahoma skies crying out "London's Burning" and folks who wrote about the music, too.

You can hear it in Greil Marcus's voice here as he defends the band's choices against a "sniveling backlash, even if they include objective mistakes, on its second album--the one first released in the U.S., the one that immediately won this Oklahoma kid over to my new favorite band in the world. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/give-em-enough-rope-86673/

And it was a world band. Marcus's description drives that home with references to "a world upside down, a world in which no one can be sure where they stand" and "a world in flames." The Clash handed me a bigger vision of the world than I'd ever imagined before, and it was all as immediate as rolling thunder drums and stabbing guitar. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_6UTZb-_vI

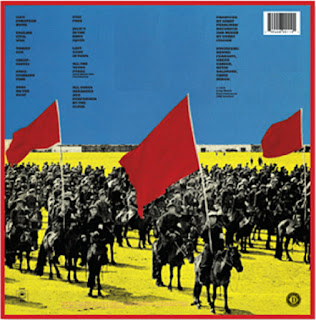

I'm not sure whether I read this review before I spotted this album on display at Bartlesville's Siegel Sound or after. I immediately picked it up because, though I'd been hearing about punk rock and the Clash in particular for some time, I'd never seen a Clash record before, and the Sex Pistols still seemed to me more like some kind of media stunt than the brilliant challenge I would later appreciate them for being. American "punk" was either still relatively obscure ("The Ramones") or labeled differently, so I heard folks like The Talking Heads and Blondie as miles from each other much less a movement. Where The Clash did fit in was in some trajectory I'd followed that year from Lou Reed to Patti Smith to Bruce Springsteen while, at the same time, falling in love with the Who moments before Keith Moon's death.

The thing was, when I put The Clash's first stateside release (the second album) on my turntable in January of 1979, I had no idea what to expect. What I heard immediately thrilled me like few listening experiences in my life, maybe like no other. Most things grow on me slowly. Of all of the above named artists, only The Who grabbed me by the throat in a similar way when I saw their video for "Who Are You" on Wolfman Jack or Don Kirshner or something. I was buying records the next day. Opening cut, "Safe European Home" sounded so surprising, so energetic and massive and crackling hot I wouldn't have been much surprised if my turntable had burst into flames.

Yeah, Pearlman's production was messy--it's the muddiest of The Clash's records--but I didn't know what they sounded like before, so I wasn't going to argue with the most thrilling mess I'd ever heard. It's a huge sounding record, on one level, but it felt somehow more relatable than almost anything else. To those punks who found it a slick sell out, I can only say we have very different definitions of "slick," since that word suggests precision and clarity to me, and nothing about this album sounds particularly precise or clear, but it does hit relentlessly hard from beginning to end. After Marcus points out "the sound seems suppressed: the highs aren't there," I think he zeroes in on why it reached me so directly, calling it "accessible hard rock" that's "fast and noisy....with lyrical accents cracking the rough surface." What he doesn't capture there, he finds in the review as a whole, with lines like, "'Give 'Em Enough Rope' means to sound like trouble, not a meditation on it."

Oh, it did. And it changed my life for that very reason. I would never hear music the same way again, and I would never see the politics of my hometown or the politics of the world our corporate town harnessed the same way again. This was, after all, just a couple of years before a series of massive lay offs that would eliminate half of my friends' parents' jobs.

Oh, it did. And it changed my life for that very reason. I would never hear music the same way again, and I would never see the politics of my hometown or the politics of the world our corporate town harnessed the same way again. This was, after all, just a couple of years before a series of massive lay offs that would eliminate half of my friends' parents' jobs.

So, criticism as consumer advice would probably write this record off as something only for the completionist or advise playlists include only "Safe European Home" and "Stay Free." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FuYzsrYSQx4 Academics could argue whether it solidified punk's rockist impulses by reaching for an American producer of a major rock band or liberated the music by the very same mechanisms. Those are fine things to do for specific reasons I suppose, but they don't motivate me. I want to thank the band for taking an unpopular risk and introducing themselves to the American heartland with sounds that hooked me and offered me a big chunk of the rest of my life. It was this album that did that. Though it only reached as high as 128 on the Billboard 200, that still means it probably had a similar effect on more than a few other kids, pushing the first album (released second) two positions higher (126) about six months later.

We were a part of the music, too. The fans always are. And that means something new every day (with each new sound and each discovery of old sounds) about who we can be. That's why I chose to write about music 33 years ago, and that's why I can't ever, really, give it up. That'd be like giving up on air or water or life itself. It'd certainly be giving up the path this explosion of righteous noise sent me down back in 1979.