Over the past two weeks, I took part in the Facebook game where you are supposed to post the covers of 10 albums that have meant and continue to mean a great deal to you. Since I have a terrible time choosing between favorites, I decided to pick 10 albums that a) changed the way I hear music and b) are little known or don't seem to get the attention I think they should. By day three, I had two friends ask me to provide some writing (a violation of the rules of the game, but an invitation I couldn't turn down). After I did this writing, I didn't want to lose it, so I've compiled it here because, well, I think these things matter. DA

#1. Aaliyah, "One in a Million"

Grief is a strange thing. I've maintained my composure when those closest to me died, even teaching class within twenty minutes of hearing an absolute best friend took her life. When Aaliyah died, I absolutely fell apart. Only Lauren, my girlfriend at the time, knows the truth of this. Lord, I must have traumatized her.

Why did the death of a 22 year old singer so tear up a 37 year old music journalist?

I suppose I was grieving many things at once, but it was only Aaliyah who could have provoked that reaction.

After the exuberance of hip hop in the late 80s and early 90s (which seemed truly the last expansive musical revolution, ripe with possibility and vision), after the deaths of Tupac and Biggie, after the thinning of a movement of women artists who dominated the charts until just about the moment this album came out, I'd hitched my wagon to Aaliyah's star.

And I did so because of this album, on which she defined an aesthetic unlike anyone else. Yes, Mary J. Blige earned the title Queen of Hip Hop Soul, but Aaliyah was a contender, perhaps not from the moment of her debut, but certainly by the time she made this record. She explains her singing style by covering Marvin Gaye's "Got to Give You Up," Gaye's sweet, sensual style a model for her voice. But the thing that made this album truly something new was the way that voice danced all around and all over and slinkily around and through producer Timbaland's staggered, edgy beats. In the same way Eric B. & Rakim's debut seemed like an elemental exploration of the elements of hip hop, Aaliyah's voice defined possibilities for hip hop soul that others have imitated but no one has come close to capturing.

That's because, I think, no one can capture a soul, whatever a soul may be. Aaliyah didn't belt and shout like so many of today's singers. She did just the opposite. It always felt she created a greater tension by holding back, by rendering her emotions with sleek, smooth control. She practically whispered in your ear. Still, she used that voice to convey every emotion imaginable in the short time she had to say what she needed to say.

I don't believe she ever made her best album. Objectively, that would probably be her last, but she was poised to blossom for years to come. This album, her breakaway from R. Kelly, promised as much, and, like Aaliyah herself, it's forever sacred in my heart.

#2 Warren Zevon, "Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School"

Maybe it was the fact that I was a viola player until graduation, but this record, Lou Reed's Street Hassle and Van Morrison's Into the Music, all grabbed me when I was still in high school in part because of the way they used strings. In this case, Zevon contrasts these sweet classical interludes with rock so hard it doesn't seem right it came from California, or from a cohort of Jackson Browne's. The opening song--with its repetition of "down on my knees in pain"--speaks very directly to me about everyday struggle, and the way it sets the struggle as a hard pratfall in a dance class fits the overall juxtaposition of the record in a way I still find thrilling. The polar opposite of the title track is my equally favorite moment. While this record is bare-fisted fight rock 80% of the time, "Empty-Handed Heart" may be the most delicate love song conceivable in this setting. And it still gets to me the way it always has--like, I need to pull over when it comes on in the car.

#3, Eric B. & Rakim, "Follow the Leader"

"No dictionary's necessary to use

Big words do nothing but confuse and lose

From the first step, a concept was kept

To the end of the rhyme, it get more in-depth," "No Competition, Eric B. & Rakim

Big words do nothing but confuse and lose

From the first step, a concept was kept

To the end of the rhyme, it get more in-depth," "No Competition, Eric B. & Rakim

My friend David Cantwell had two albums framed to hang on my wall because he knew just how central they were to my soul and sensibility. They're still on my wall after who knows how many years. One is Bruce Springsteen's "Darkness on the Edge of Town," the record that, in many ways, shaped my identity in relation to music. The other is Eric B. & Rakim's "Follow the Leader," a record I obsessed over the year we met, the year I started my first paid writing job,1988, an incredible year for hip hop. Released one month after Public Enemy's "It Takes a Nation of Millions," the same day as Salt-N-Pepa's signature "A Salt with a Deadly Pepa" and just a couple of weeks before N.W.A.'s "Straight Outta Compton," "Follow the Leader" was a key player in a wave of ambitious leaps that would forever change the boundaries of hip hop.

From the moment I met my friend William Heaster and he gave me a cassette of Eric B. & Rakim's first album, '87s "Paid in Full," I went from being a casual rap fan to a fanatic. (Like many in my era, I'd been shaken by Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five and any number of Run DMC tracks.) But Eric B. & Rakim's "Paid in Full" took me somewhere else altogether. I think there's an interesting parallel between the first generation of rock and rollers and the self-conscious (as in self aware) rock and soul musicians of the 60s. Rakim's lyrics took hip hop apart and examined the elements; Eric B.'s beats and scratches were as absorbing as any rock sax or guitar. That is a perfect album, as stark and bracing as this follow up is lush and sweeping. It's really like picking between "The Godfather" and "The Godfather, Part II" to weigh one against the other.

The key difference, like so many rap records in '88, was a fuller, faster, more frenetic sound. After hearing the incredible Coldcut remix of "Paid in Full," "Follow the Leader" sounded like a sequel as an extension of that reimagining of sonic possibilities. Rumbling bass prowls just under a mindboggling array of beats, whirling dervish disembodied voices, stabs of horn and strings and Rakim's verses, "traveling at magnificent speed across the universe." Rap had absorbed the history of rock and jazz and soul and freed all of it from any sense of limits.

Central, of course, to all of it were Rakim's distinctly urgent but cool vocals. This MC refused to shout to make his points--he kept his white knuckled attack sleek and, as I remember Greg Tate described so eloquently at the time, lethal. On a quiet track like "The R," with its eerie late night keyboard, you can hear a prophecy of "The Chronic" and Snoop Dogg.

But Eric B. & Rakim never fell into the sort of nihilism that would soon overtake so much rap. Rakim's contemplation of the elements of his art--Eric B.'s fearless scratches and beats, the audience both in the crowd and at home, and the expressive weaponry of the MC's verbal dexterity--all served the cause of personal and communal liberation. I know I was never the same, and the many samples of this music that would infuse hip hop future show I wasn't alone.

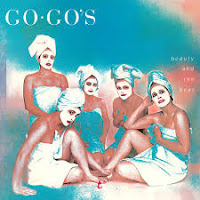

#4, Go-Go's "Beauty and the Beat"

Before the Go-Go's, the women I listened to--Patti Smith, Chrissie Hynde, Rickie Lee Jones, even Stevie and Christine of Fleetwood Mac--were, to varying degrees, exotic counterpoints to the male artists I identified with more directly. (It's probably worth noting, at that point, I still thought of soul as my mother's music and country as my father's music, so the sounds that would later overtake me weren't factored into the equations much.) The Go-Go's were certainly distinctly feminine, so clearly being girls, but I identified with them the way I identified with male artists. I feel like it must be somewhat parallel to the way many young women experienced The Beatles differently than other male artists. And it so appealed to me on a par with any artists I loved--particularly Charlotte Caffey's fine songwriting--that I forever opened up to sounds the little boys aren't supposed to understand. At 17, this was a very big deal....almost forty years later, it still is.

#5, Karyn White, "Karyn White"

In 1988, I was 8 years into a relationship and four years into a marriage, and I found myself seeking--often bold, accusatory--therapy in music made by women. I'd been prepared by Janet Jackson, Pebbles and Salt-N-Pepa, but Karyn White's album-length blend of the excitement of hip hop and the maturity of soul hit me right where I lived. I needed both of those things in the equal measure allowed by her tender-tough vocals and brilliant production by L.A. Reid and Babyface. My constant play of this record in 1988 (one of my first Pitch reviews, along with a very similar record by Angela Winbush and Mariah Carey's debut) has everything to do with the Mary J. Blige book I wrote almost three decades later. In fact, I start the book with White.

#6, Ian Hunter, "You're Never Alone with a Schizophrenic"

I can't overstate how important this record is to me. I didn't know Mott the Hoople as anything more than a name when this record came out (though "All the Way from Memphis" was featured in one of my favorite movies). I'm sure I bought it because Max Weinberg was on drums, Garry Tallent was on bass and Roy Bittan played keys. But from the opening beats of "Just Another Night," I realized this wasn't the E Street Band I knew. They seemed to be playing with more abandon, hitting even harder (and that's saying a lot) and, in some ways, shooting farther. The sounds here blended every aspect of rock that had drawn me since childhood--it was grand, sometimes even psychedelically textured and colored, always excited and exciting. It was also just the record for a variety of purposes. At the end of the day, my brother Kent and I would put this on in the darkness of our room and fall to sleep to it. But when it came time to face the real world, its brash-punk sensibility suited the fight. Songs like "Bastard" and "Standing in My Light" helped me navigate high school halls. One of my favorite songs ever was the manically agitated "Life After Death," a way-over-the-top rocker played hard enough to earn every bit of its call for everyday resurrection. Did I believe? Do I believe? "Oh yeah!"

#7, James Blood Ulmer, "Are You Glad to be in America"

I'm 17 and about two years into an exploding musical universe that has changed how I see myself, the world around me and my role in that world. Two years before, I'd seen and heard Ornette Coleman on SNL--I remember one of my older brother's friends dancing across the room to that horn, and from that moment on I'd been fascinated by this mysterious separate set of rules Coleman called harmolodics. But this album by Coleman's student Ulmer turned that fascination into something very intimate. It's a dischordant, intoxicating funk--in which horns, guitar, and drums attack a revolving center and throb like lift-off--in some perfect balance of frenzy and suspension. It took me all day to even think about putting words to this one because it would take me days and days to get at why this is a go-to record for me. But if I need to be shocked out of a stupor and back into life, this does it every time.

#8, Ruben Blades, "Nothing But the Truth"

In 1988, I was being radicalized by Iran-Contra. A lot went into that, starting with The Clash's Sandinista and climaxing with the Sun City record. I'd joined Amnesty International first, and then become involved with Oklahoma City's Peace House. I'd met Benjamin Linder's parents (he'd been killed by Contras while helping Nicaraguans with a hydroelectric dam), and I knew refugees from El Salvador. I'd met women who lived under apartheid and gave me a perspective I'll never forget. The anti-apartheid movement informed my own efforts on campus to help with the Black Student Union's fight against David Duke and the Klan's evangelical works on campus. I was awakened to the complicity of this superpower's fundamental structure when I saw Oklahoma Democrat David Boren throw softballs to Oliver North during the hearings. The death of murderous Guatamalen dictator Rios Montt this week--a man trained, heralded and supported by the U.S. government for the open genocide of Mayan Indians--is a vicious reminder of how much my perspective of the American ruse came clear during those years. And along came Ruben Blades' first English-language album. Undoubtedly not his best album, but crucial in my development, finding a solid link between the Lou Reed and Elvis Costello I knew so well and the politics and the music of this exploited world that preoccupied my mind. For what it's worth, I think it's a gorgeous record, and it holds up, not just for its indictments of the dictatorship in El Salvador and the hero-worship of Oliver North, but for it's gentle reflections--songs like "Letter to the Vatican" and "Hopes on Hold," with lyrics throughout engrained in my psyche as firmly as any music anywhere. And then there's that voice. Very few have ever sounded so sweet on a blue note, and his hat tip here to Marvin Gaye shows he knows the debt he owes.

#9, Cidny Bullens, "Somewhere Between Heaven and Earth"

"There's no rhythm in the rain/There's no wishes in the stars/There's no power in this pain..."

It's so strange to hear this record with my dad gone. He loved it. I remember him absently scratching his side the way he'd do and saying "That 'Boxing with God...'" He'd then be thinking through the right words to convey what I already knew. It's how Dad experienced life. It spoke for his constantly questioning sense of faith. Every day was a struggle.

Of course, hard focused on the the death of Cidny Bullens' 11-year-old daughter Jessie, "Somewhere Between Heaven and Earth" is ten bloody rounds, even in the album's closing defiance. "I might be going down, but I'm no quitter," Bullens declares over hard guitars and pounding drum. It's the plain truth you hang onto while this parent sings through grief in the starkest possible terms. (I'm doing good not to crumple right now while Bullens' other daughter Reid sings her refrain on "As Long As You Love.")

This one's been on my mind a lot lately, in part because of Bullens' work for the Columbine families. But I'm two decades older, now. I live with losses I never could have imagined then. My friends know loss they couldn't have imagined either, and that I can't quite grasp. This album takes all of that on, with remarkable beauty and strength. It's a truly singular gift, fashioning power out of powerlessness, then passing it on.

#10, The Beatles, "The Beatles Again" or "Hey Jude"

"For well you know that it's a fool who plays it cool by making his world a little colder."

When I heard the Beatles broke up, I was 6 years old, standing in the Bartlesville, Oklahoma Pennington Hills IGA with my mom, doing her weekly grocery shopping. I picture it as the cover of a checkout tabloid, but I believe it was simply part of the many conversations my mother would have with the people who ran the store and other shoppers.

That summer I would buy my first 45 at a mall in Atlanta, Georgia. It was War's "Spill the Wine," seemingly part of the constant AM radio soundtrack of the family trip. I loved the sly funk on the back side of that single's ""Magic Mountain" maybe even more than the hit. "We're going high, high, high, and never coming down!"

That Christmas, my brother James gave me "The Beatles Again" (also called "Hey Jude"), what I presumed to be the band's last album. We moved that year, a hard change for me, and I remember playing that record over and over and over again in the rec room of that new house. The second side opener, "Hey Jude," in particular, is the song I think of getting me through that move and the dissolution of my family--my parents fought hard in the years leading up to their divorce, and my teenage brother began to hit the road when he could. They were each there for me individually, but I wanted the band together. That wouldn't happen again, but I'd always have the record.

I'd always known the Beatles. I kind of thought they were music or something--them, Elvis and Stevie Wonder. Arriving on Ed Sullivan when I was four months old, they were always in the air. But it's funny to think of the way my 7 through 10 year old self heard this as a selection of songs recorded together in the studio. Album opener "Can't Buy Me Love" was released one month after the mop tops hit American shores, and the songs that really defined the album for me--"Revolver," "The Ballad of John and Yoko," "Don't Let Me Down" and "Hey Jude," conveyed the band's fully mature hard rock grandeur. (If that doesn't sound like "Hey Jude," you're forgetting the final four minutes.) Sure, four years of recording doesn't seem like a lifetime's distance, but it was for The Beatles, who looked for all the world like old men on the album cover. (The oldest Beatle, Ringo Starr, was 29 on that shoot.)

At least to my admittedly biased ears, producer Allan Steckler made smart choices from the many B-sides and non-album singles he used. He managed to fold all of the Beatles' chapters into a solid whole, "Rain" and "Paperback Writer" representing brilliant polarities of the band's mid-career studio ambitions. But maybe that's just the wonder of happenstance with such great music. Either way, the collapsed boundaries between shining pop, hard rock, soul and even a kind of funk had more to do with shaping my sensibility than I'll ever know.