|

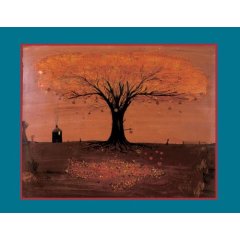

| Bradbury's Halloween Tree |

Ray Bradbury, The Halloween Tree

I remember being by the side of my bed, staring at a quilt my mother made, when I first understood that I was going to die. I don’t remember the situation, the details of how I asked my mother or how she tried to cushion my understanding, but I remember the fact of having asked and having been told that all of us would die one day, and it was later, in my room and I was down on my knees on my floor, looking at the bed.

I was very young, maybe no more than 5 or 6, but the new questions rushing through my brain trumped all the answers I’d ever received, particularly from people who’d also handed me the wonderful magic of Santa Claus and a tooth fairy. Why was I so lucky and why was I so cursed?

I suppose I'm lucky that I always felt lucky to have been born. And I know I was very lucky to have two loving, nurturing parents and an equally gentle and kind older brother to make me feel secure in those early years.

But I am also in some ways grateful that family broke apart by the time I was 10 because I may have had an even harder time with change than I do. More vividly than that old quilt, I can see my parents holding hands, my mother sitting beside me on the couch and my father sitting on the ottoman in front of me telling me that they weren’t going to be living together anymore. People think it’s odd when I tell them this, but my parents took me out to see the movie The Sting right after that announcement, and that’s a bittersweet, precious memory. Something had died, and I was in shock, but I was also with my parents, and I could tell I was going to live. In all the pain, and it was deep, there was even a flutter of excitement that with this death came new possibilities.

Those endorphins didn’t mean I was out of the woods. Though I have warm memories of those next few years, living with each of my parents separately and getting to know them better as individuals (and feeling what everyone wants to feel in their junior high years—grown up), I still yearned for things to go back the way they had been.

I felt closer to my parents than before, but adulthood did not seem like a happy place. The forces that drove my parents to separate rather than adapt and deal with each other seemed as obscure to my parents as they were to me. And other adults didn’t seem happy either. My harried teachers in their odd polyester outfits, the ashen-faced and rumpled white collar workers who I sold newspapers to after work, my friends’ parents who generally seemed cold and severe (at one extreme, or overly emotional and a little bit scary at another), all of these adults told me something went wrong when we grew up. As a child, I think I associated the smells of coffee and beer with that thing that went wrong.

Okay, this is a heckuva leap, but I think it's worth it. It seems to me that these childhood perceptions parallel Western Civilization’s dominant conception of evil, particularly vivid in Christianity. The King James Bible’s Gospel According to John states, “In the beginning there was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” What follows is the fall of Man, the Word made flesh and sacrificed to redeem Man and a struggle between Good and Evil that results in the Apocalypse of the Book of Revelations, a happy ending to a story of continuous moral decline.

This generalized perception that the past is somehow closer to a divine order and the future is a continual movement toward decadence is pervasive in our society. One constant assumption I have to talk about with my students semester after semester is the perception they have had drilled into them that their parents’ generation was somehow more wholesome than they are. Though it’s fairly easy to show that the rates of violent crime, drug use and sexual promiscuity were higher when I was a child in the seventies, my younger students tend to equate their parents’ childhood (roughly the same era as mine) with some kind of Ozzie & Harriet or Brady Bunch neverland. Some don't of course; some grow up without any such illusions, but as a group, it's still a common myth among my students.

This nostalgia overlooks a lot of nasty reality, such as the racial segregation that was barely beginning to lose hold in my youth (and is still vividly alive in so many ways today). Nostalgia makes it easy to equate any advances in scientific understanding or technology as corrupting to the human spirit. We may not really want to live in the past, but an unexamined assumption that underpins most discussions is that the past is better, and the future is something to dread.

|

| The Wolfman, 1941 |

So far from the God end of the axis, no wonder sexuality lies at the base of so many moral arguments. No wonder Jesus’s virginity (not to mention his miraculous fertilization) still fuels popular debate. Sexuality ties together both concepts of the linear movement away from God—chronologically, our growth out of childhood and, conceptually, the development of our drive for sensual pleasure, Earthly pleasure. Complicating things even more, we tend to describe spiritual illumination in very similar terms as those we use to describe sexual ecstasy, which all of the above paradigms suggest must be tainted by evil. What a mess!

|

| Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, 1931 |

At its base is the fact that I feel like a kid watching a horror movie, and the fear tends to be a precious reminder of childhood. A kid at the center of the action is also archetypical of horror stories as varied as A Turn of the Screw, The Exorcist and Salem’s Lot, which certainly helped me bridge the gap between children’s books and adult novels as a preteen.

I think it was my own ambivalence over a loss of innocence that drew me to Ray Bradbury’s stories and novels. Whether he was dealing with the potential loss of a friend to illness in The Halloween Tree or the magical properties of Dandelion Wine or the threatening world of the exotic carnival in Something Wicked This Way Comes, part of what I could hear in that voice was an echo of my own pain over a loss of innocence and a capacity for wonder. Many attack Bradbury’s purple-ish prose, but as a fan I can testify that it is the child’s ear in that poetry that gives Bradbury’s writing its essential magic.

|

| Graphic from original IT hardcover, 1986 |

At the same time, and this is the sort of thing King doesn’t get nearly enough credit for, It complicates this nostalgia by making plain that the horror predates the child and it is an inextricable counterpoint to the wonder of childhood. Puberty plays an essential role in defeating the monster, and the protagonists never really win the war until well into their adulthood, by invoking their child selves as adults.

But King’s complex take on the question aside, it’s easy to see why we fear the future (with or without a particular philosophy or theology to back us up)—to catalog all of the various takes on horror in the future tense is to list (only sometimes metaphorically) the many ways we are screwing up our world. And, not incidentally, the reason kids notice adults hitting that caffeine in the morning and alcohol at night just to make it through another day.

http://www.amazon.com/Halloween-Tree-Ray-Bradbury/dp/1887368809/sr=8-3/qid=1162245173/ref=pd_bbs_sr_3/102-3149483-3364948?ie=UTF8&s=books

http://www.amazon.com/Signet-Books-Stephen-King/dp/0451169514/sr=1-1/qid=1162245263/ref=pd_bbs_1/102-3149483-3364948?ie=UTF8&s=books

No comments:

Post a Comment