Like most of us, I was born into a haunted house. For one thing, I was born amidst assassinations that shook my family caught up in the Civil Rights Movement. Medgar Evers was killed in his driveway four months before I was born. One month before I was born, a bomb in a Birmingham church killed four young women--Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Diane Wesley and Carole Robertson--young women symbolic of the Movement youth transforming the country at the time. When I was one month old, the President’s assassination traumatized my family of Democrats, and a bust of JFK stood sentinel in my home from my earliest memories.

Like most of us, I was born into a haunted house. For one thing, I was born amidst assassinations that shook my family caught up in the Civil Rights Movement. Medgar Evers was killed in his driveway four months before I was born. One month before I was born, a bomb in a Birmingham church killed four young women--Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Diane Wesley and Carole Robertson--young women symbolic of the Movement youth transforming the country at the time. When I was one month old, the President’s assassination traumatized my family of Democrats, and a bust of JFK stood sentinel in my home from my earliest memories.My older brother’s music filled the house, and an early memory of mine is listening, with my parents, to Dion’s “Abraham, Martin and John” on my brother’s stereo. By the time I was 7, the Beatles had broken up. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison died within about a year of each other. By the time I could read my first picture book, the 1960s and my Kodachrome childhood guttered away.

We would have dealt in ghosts anyway. My mother’s side of the family was from Louisiana, and ghosts quilted the fabric of their stories. By the warm end table light in the little apartment where my grandmother lived alone, she told and retold these stories. As a young girl, her mother watched the former lady of her plantation home, long dead, transparently descending the stairs at dusk. As hard nosed and salt-of-the-earth a matriarch as you can imagine, my great grandmother Julia’s life was filled with such moments.

My grandmother’s little brother, whom she had watched over as a girl, had been killed in accelerated pilot training at Waco during World War II. Some snafu at the control tower led his plane into the air as another was landing. My grandmother said he held that plane where it descended like a leaf, so that the student might jump out. Neither one did. Later, at James’s funeral, my grandmother and mother both remembered that the coffin didn’t look long enough for his body. My seven-year-old mother felt his hand on her shoulder as she had this realization. For a while after her Uncle James died, my mother wouldn’t let anyone take James’s seat at the table.

Not long after that, my grandmother’s still young husband died. He’d had rheumatic fever as a child and never had a strong heart. Perhaps that was why he lived the active way he did. He was a forensic scientist who made trips to research malaria in southern Louisiana, and he was a saxophonist in a swing band and a choir director at their church in Shreveport. He loved entertainers, and my mother’s love of movies came out of his. He was friends with Jimmy Davis, who wrote “You Are My Sunshine” as well as Emmett Kelly and the puppeteer behind Kukla, Fran and Ollie. Grandma always joked that she never knew when he might bring circus people home to supper. After the picnicking and fireworks of July 4th, 1944, my grandfather woke up with a heart attack, and he was gone.

My mother, grandmother and great-grandmother all lived together after that. During my mother’s adolescence, my great grandmother came in the house from the front yard where she’d been consulting with a tree doctor about the sick elm in the middle of the yard.

“Mary,” she told my grandmother calmly, “I need to go to the hospital because James has come for me. It’s my time.”

“Oh mother,” I can hear the disgusted tone my grandmother used when she answered, “You’re fine.”

But she insisted, and my grandmother took her to the hospital, and she died within a couple of hours. My mother said she never saw anyone die so peacefully.

Odd as it may sound, some of my warmest early memories are these--sitting by my grandmother on the couch, prompting her to tell one story after another as the goosebumps stood up on my arms, tears came to my eyes and shadows in the room began to come alive and crawl.

Looking back now, I see that Grandmother’s ghost stories served several different purposes in my childhood. They conveyed a part of my heritage. An Ecuadoran student once told me that, to her, the Latin American brand of surrealism, magic realism, seemed like a way the authors showed respect for their elders and the stories they told, the way they told them. (For what it's worth Gabriel Garcia-Marquez said the same thing.) I understood exactly what she meant because I thought of my own grandmother. That’s an important connection because the Southern gothic and magic realism both make sense when looked at that way. The two traditions share a rebelliousness in their very desire to celebrate some of the most subjective and vulnerable aspects of who we are in the face of a changing world.

This theme is repeated again and again in horror—in tales of the vampire and the werewolf, even in the demon possession of The Exorcist, the arguably definitive modern horror story for the way it romanticizes denigrated past beliefs in its war with the conventional wisdom of the present. Even the awakening of those goosebumps, teary eyes and shadowy hallucinations serves as a sort of subjective communion with a way of thinking and feeling that is certainly primeval.

But the telling of those ghost stories also served another, less mystical but very likely more important, purpose. They brought my grandmother and I (along with my mother and my brother who also shared in this tradition) closer together. If one of the themes of horror is our fear of being alone (the bottom line in Frankenstein, for instance), it is important to see that the telling of the scary story is generally a collective experience. Even if one is simply reading a book (an act Stephen King has called a sort of mental telepathy), the writer and the reader are joined in the experience of confronting that which makes us feel like we are alone, together. This too is important. All of these concepts unite people despite their sense of isolation.

My grandmother lived most of her life alone, but she never seemed terribly lonely. I would guess a part of her strength came from her communion with her ghosts—none of the many people she lost in her life ever seemed far from her heart or mind. What she definitely passed on was a sense of connection. To this day, when my brother and I talk about our grandmother, we admit we still feel like she is right here with us. When we’ve each been at our lowest, we’ve gained a sense of unconditional love and strength from this sense of our grandmother’s presence. Whatever the spirit is, it finds sustenance in this sense of the otherworldly that comes through the ghost story. Though much of the value of understanding our monsters and horror has to do with what we fear, it is essential to keep in mind that the tale of what we fear offers a balm, a sense of communion with others, at the very least, in our shared fears.

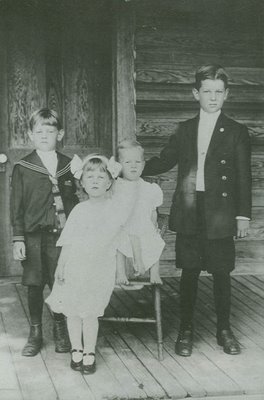

(In the picture--Nana and her brothers; (l-r) Lewis, James and Francis)

No comments:

Post a Comment